The BIG Question:

Is it ethical for forensic scientists to use DNA databases containing the genetic information of people to identify suspects in crimes?

Critics of DNA Fingerprinting

37 years after DNA fingerprinting was discovered by Professor Sir Alec Jeffreys, DNA typing has become an integral part of modern crime-solving. The National Database of DNA has grown exponentially. Now, many individuals are concerned about personal privacy when information is not only stored about criminals but about a much wider range of people.

Interpretation and Human Bias

In Itiel E Dror and Greg Hampikian’s 2011 study, when 17 North American expert DNA scientists with around 8.9 years of experience each interpreted a single DNA mixture collected from a real adjudicated crime scene, they produced inconsistent conclusions, suggesting subjectivity and bias [4].

In fact, only 1 interpreter out of the 17 gave the same conclusion as the original crime scene conclusion [4].

According to Dror and Hampikian, the knowledge of each interpreter about the investigation of the crime impacted the interpretation of the DNA sample. For example, an interpreter may analyze information in a biased way to fit their own existing beliefs, hopes, or motivations [4]. If DNA fingerprinting was truly objective, then all of the examiners would have reached the same conclusions.

This may lead to the wrongly accused individuals ending up with emotional or reputational damage, negatively affecting them in their future careers and life.

Furthermore, It has been long believed that DNA is the “gold standard” of forensic science, free of all subjectivity. The supposed accuracy of DNA fingerprinting results leads investigators to not pursue a larger range of suspects, as they believe that the suspect in the DNA sample is the only one, when the DNA sample may have been interpreted incorrectly.

Racial Considerations

According to many legal scholars such as Hank Greely and Dorothy Roberts, there are more African and Latino individuals who are already in the databases of the criminal justice system [1].

Indeed, in 2010, African Americans accounted for 27% of all adult arrests when the total Black population was 12%. In other countries, African Americans make up 52% of the population and account for over 85% of arrests [1]. This leads to more African Americans having their DNA in a national database than other races, leading them to have a higher likelihood of a match with another suspect's DNA.

Privacy Concerns

According to a study by David J. Kaufman, the public is very concerned about genetic privacy and who has access to their DNA information [6].

A survey of 4659 U.S. adults revealed that:

- 90% would be concerned about privacy

- 56% would be concerned about researchers having their information.

- 37% worry study data being used against them in criminal investigations

Interestingly, when needed, people are more willing to participate in DNA collection:

Within that same survey...

- 60% would participate in a biobank if asked

- 92% would allow academic researchers to use study data

- Concern about privacy was related to lower willingness to participate only when respondents were told that they would receive $50 for participation and would not receive individual research results back.

This shows that even though people are concerned about their privacy, they are still willing to provide data to researchers if necessary. This willingness of the public matches up with the research on the previous page, in which the overall sentiment of DNA fingerprinting was positive.

Many individuals are also worried about the potential of the use of their genetic information to discriminate: for example, getting different kinds of insurance coverage for different prices based on medical history [7].

In 2012, privacy concerns lead the United Kingdom to pass the Protection of Freedoms Bill, requiring that all DNA samples be destroyed within 6 months of being taken. As a result, about 1,766,000 DNA profiles of innocent adults and children were deleted from the database [8].

Supporters of DNA Fingerprinting

Supporters of DNA Fingerprinting believe that the practical applications of DNA fingerprinting and its ability to both solve the crime and settle paternity disputes outweigh privacy concerns.

Ability to Solve Crime

It is much harder for the average individual to prevent the shedding of DNA extracts such as hair follicles, skin flakes, and saliva. In contrast, when needing to take an actual fingerprint, a criminal could wear gloves to cover up their tracks, effectively blocking the investigation.

In fact, DNA fingerprinting was used to arrest the Golden State Killer of 2018, someone who killed at least 13 and raped 50 innocent people. Court documents describe how DNA collected from semen at a crime scene was used to search a database on GEDmatch, a free service that allows individuals to discover their relatives and ancestors. Coincidentally, Joseph James DeAngelo’s profile made a perfect match. Afterward, police needed to confirm the identity of DeAngelo before making the arrest. Law enforcement “lifted traces of DNA” from DeAngelo’s car door while he was shopping at Hobby Lobby. This DNA was compared to genetic fingerprints captured from semen gathered at previous crime scenes. After confirming a match, DeAngelo was arrested on the spot, putting an end to his decade-long eluding of law enforcement [5].

Solve Paternity Disputes

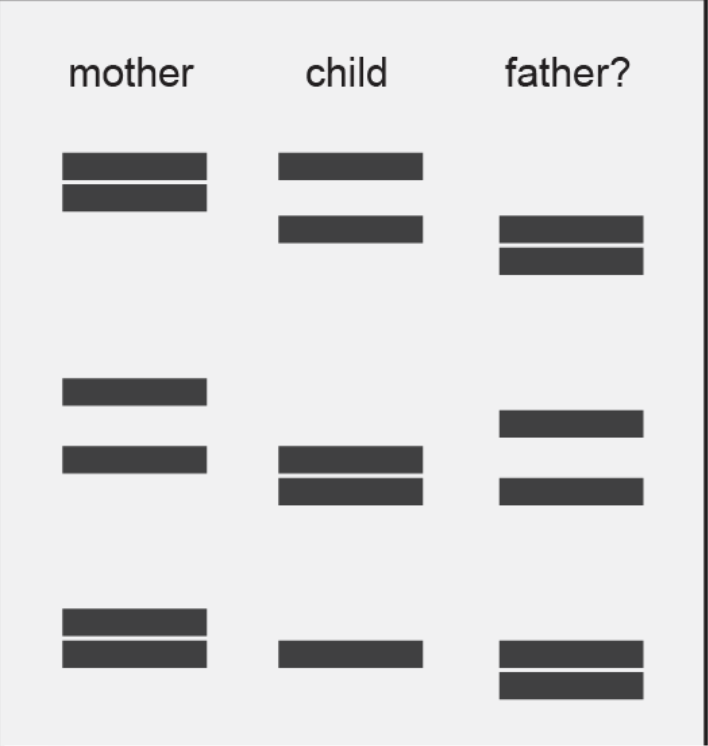

Even though the all humans share 99.9% of all DNA, there is still 0.1% that differs between us all. Within that seemingly small difference in DNA, children will have even more DNA in common with their mothers and fathers than complete strangers. When the DNA fingerprint for a child, mother, and father are taken, they can all be ran through gel electrophoresis. A suspect father is more likely to be the biological father if more of his DNA position matches the child's DNA position on the gel.

In the example above, the child inherited DNA from the mother and the father in multiple sections, meaning that the candidate mother and father are likely the child's biological parents.

Conclusion

Depending on the perspective, there are drastically different views on the ethics behind DNA fingerprinting. Some people believe that having a national database of everyone’s DNA on file is unethical and is an invasion of privacy, while others argue that the potential of DNA fingerprinting to solve crimes and outweighs the drawbacks.

While it is important to acknowledge the benefits and disadvantages to each side, there are some ways that may be both ethical and agreeable to public opinion to collecting DNA profiles.

One such method would be to have a voluntary system of DNA collection. Similar to a blood drive, individuals could register their DNA into a national database maintained and encrypted with the highest security. By having genetic information stored, the volunteer is able to be proved innocent in a crime scene investigation. On the other hand, forensic scientists are also able to have another person’s DNA in a repository to assess whether or not someone is part of the suspect pool.

Another way of collecting DNA would be to only collect the DNA of those who are arrested. Since someone was arrested once, and should they be set free eventually, they may have a higher chance of committing a crime again. In such a case, the DNA fingerprint of the person, while they were arrested, would link them as the perpetrator of the second crime. The basis for this method stems from the fact that 83% of state criminals released committed another crime within 9 years of their release [2].

References

- Ahmed, Aziza. “Ethical Concerns of DNA Databases Used for Crime Control.” Bill of Health, 30 Jan. 2019, https://blog.petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2019/01/14/ethical-concerns-of-dna-databases-used-for-crime-control/.

- Alper, Mariel, and Matthew Markman. pp. 1–24, 2018 Update on Prisoner Recidivism: A 9-Year Follow-up Period (2005-2014).

- De Sola C. Privacy and genetic information. Conflict situations. Journal of Law and Human Genetics 1994;1:179–80.

- Dror IE, Hampikian G. Subjectivity and bias in forensic DNA mixture interpretation. Sci Justice. 2011 Dec;51(4):204-8. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2011.08.004. Epub 2011 Sep 1. PMID: 22137054.

- Ducharme, Jamie. “How Investigators Got the Golden State Killer Suspect's DNA.” Time, Time, 2 June 2018, https://time.com/5299394/golden-state-killer-dna/.

- Kaufman, D. J., Murphy-Bollinger, J., Scott, J., & Hudson, K. L. (2009). Public opinion about the importance of privacy in biobank research. American journal of human genetics, 85(5), 643–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.002

- McGuire, A. L., & Majumder, M. A. (2009). Two cheers for GINA?. Genome medicine, 1(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/gm6

- Your Genome, “Is It Ethical to Have a National DNA Database?” Debates, The Public Engagement Team at the Wellcome Genome Campus, 19 Jan. 2015, https://www.yourgenome.org/debates/is-it-ethical-to-have-a-national-dna-database.